Do not miss the rest of the series:

- The Ethical Perspective

- A North American University Perspective

- Pause Giant AI Experiments: An Open Letter from the Future of Life Institute

- Regulators vs ChatGPT - Updated on the latest developments by regulators

- An Administrative Judge's Perspective

- A Computer Scientist's Perspective

- A Legislative Drafter's Perspective

- A Statistician's Perspective

CHATGPT is a large language model created by OpenAI, based on the GPT (Generative Pre-Trained Transformer model) architecture. As a language model, it has the capability to "understand" and generate human-like responses to text-based queries, making it an effective tool for natural language processing (NLP). It is tuned with machine learning techniques (unsupervised type) and optimised with supervised and reinforcement learning techniques. One of CHATGPT's main functionalities is to answer questions and provide information on a wide range of topics (as a chatbot). It can also generate text based on prompts, engage in conversations with users, and perform language-related tasks, such as summarization, translation, and sentiment analysis.

On 14 March, the fourth version of ChatGPT has been launched and, among the functionalities, also accepts multimedia content, such as images and videos, as well as much larger texts of up to 25,000 words. It can also capture users' writing styles and compose songs in their preferred style and increased accuracy in responses. There are various users' experimentations, including those who have asked the system to create a site, code video games, describe images and generate recipes.

The race to use and offer similar AI systems also includes giants such as Microsoft and Google. Microsoft presented a preview of its Bing search engine with AI functionality, and Google did the same with its Bard project. Opera is also experimenting with integrating ChatGPT into its search engine, including 'Shorten', a way to automatically create summaries of articles and web pages visited. Also, Microsoft announced Copilot, a text assistant with generative Artificial Intelligence for use in Microsoft 365 apps, drawing on Microsoft Graph to function, i.e. the API and software architecture that support Microsoft’s user documents, images and content.

Frequently asked questions about CHATGPT include its capabilities, limitations, and ethical considerations. Users may ask about the accuracy of its responses, the extent of its knowledge, and the potential biases inherent in its training data. Some users may also have concerns about the potential misuse of AI-generated content and the need for ethical guidelines in the development and deployment of language models. Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, opened the discussion on large-scale disinformation threats and stated “I think people should be happy that we are a little bit scared of this".

In our series, we will ask experts from different backgrounds to answer some of our questions and give their views on the opportunities and risks of using ChatGPT, and how we should relate to it, both as individuals and as a society.

Actually, we already have one guest. The host of the first issue of the series is CHATGPT itself! We asked ChatGPT to "write an essay on the risks of ChatGPT, and how (if) it should be regulated". We then asked to "add citations directly into the text, with a bibliography at the end".

The result (click here if you want to read it now) leads to some initial thoughts on the tool. What does ChatGPT aim to be? What errors are still evident? What are the concerns?

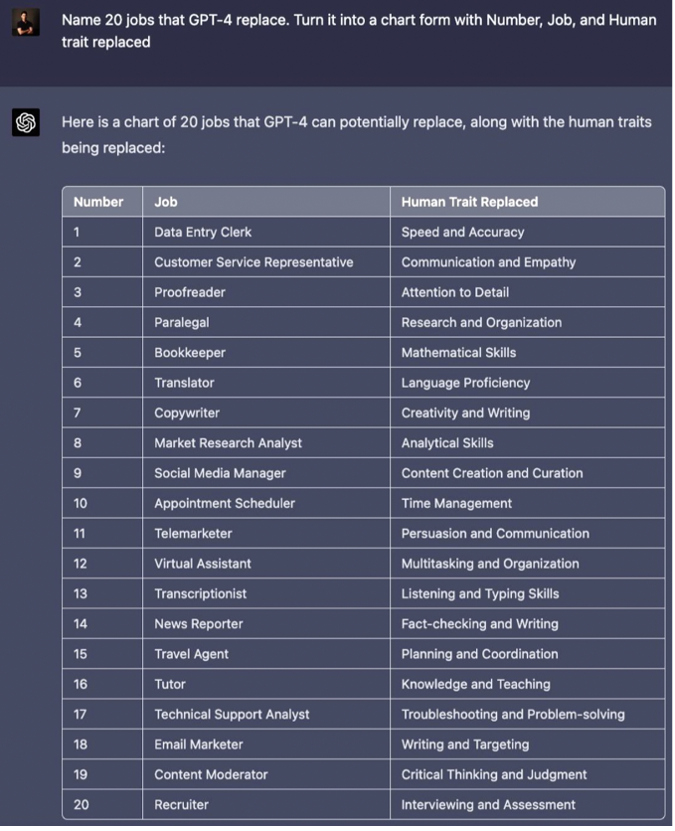

Starting from what ChatGPT wants to be, there cannot be just one answer, but each one completely changes the perspective of use. Is it correct to use it as a purveyor of knowledge to be interrogated and replace our own search for facts and information? The answer probably already lies in the fact that it is a language model, and not a knowledge one. We could see it as a trainee assistant, efficient and helpful (crashes aside), but whose information and knowledge are always to be verified. The above is not to say that the implications for society are trivial, e.g., generative AI can enhance productivity but may also lead to the replacement of human employees. Indeed, the question of which professions it could replace was asked by a user to ChatGPT itself and the answer was as follows:

Probably, at least at present, ChatGPT could not be a 100 % replacement for any of these professions. This does not detract from the fact that it could lead to fewer resources needed, reducing the workload for some professionals.

Among other concerns, the academic world is debating on the use of the system for academic research and writing. Many plagiarism detection software, able to detect the use of AI writing, already exist (one even provided by OpenAI). However, some authors are also starting to mention ChatGPT as a co-author. What are the consequences for copyright law? The Italian Supreme Court, in its Order No. 1107 of 16 January 2023, ruled - incidentally - that the unauthorised reproduction of the creative image of a flower constitutes an infringement of the copyright of the person who made the image, even if the software was used in the creative process. However, the Court clarifies that “originality must be verified on a case-by-case basis, thus ascertaining not the idea behind the work, but its subjectivity, assuming that the work reflects the personality of its author, manifesting his free and creative choices”. This is different from what happened in the United States, where the Copyright Office failed to recognise the copyright to a comic strip because it was drawn with an artificial intelligence system (Midjourney platform), even though it was under the supervision and guidance of a human. The comic strip of the algorithms, based on the interpretation, is not to be protected by copyright, as is the case for human creations: the real creator of the panels remains the artificial intelligence (i.e., Midjourney), while the human is relegated to the role of mere inspirer of the work.

Still on the academic side, a problem (which also stems from the use of this tool in relation to its current status) lies in the sources: those are often invented. The same happens in the answer it gave to our question about risks and regulation. As per the bibliography at the end of the article, almost all the sources are non-existent, while other times those are real articles with different authors. The question to ask, however, is what would happen if access was given to academic databases: what would be the result of integrating ChatGPT into an online library containing the major academic databases? We will ask one of our guests! In any case, OpenAI is aware of this 'hallucination' problem (AI system giving a response that is not coherent with what humans know to be true) and is tackling it through InstructGPT models.

Doubts naturally arise from the regulatory point of view (recently also discussed through a collection of academic contributions by The Regulatory Review). So much so that the European Parliament, through Benifei and Tudorache, has proposed the inclusion of these systems in the 'high-risk' list. An idea probably not in keeping with the use of ChatGPT as an assistant, so much so that Axel Voss stated that the amendment 'would make numerous activities high-risk, that are not risky at all'. As for the AI Act, one wonders whether the EU is actually gearing up to protect itself, not so much from the tool itself, but from its applications. The latter are indeed incalculable and dynamic and affect all sectors, and will lead to an ever-increasing scale of use. The current European approach may therefore be ineffective in the sense that it focuses on the tools (in light of their known risks), but does not focus directly on the unpredictability of future risks and related risk management. There are authors in academia who suggest that rules in the AI Act and other direct regulations must match the specificities of pre-trained models, in a perspective that directly addresses "(i) obligations regarding transparency and (ii) risk management. Non-discrimination provisions (iii) may, however, apply to LGAIM developers. Lastly, (iv) the core of the DSA content moderation rules should be expanded to cover LGAIMs".

The tool - just in its infancy - captures multidisciplinary interest and stimulate a discussion on the prospects, risks (but also simply impact on our lives) and the need for regulation. Leaving you to read ChatGPT's contribution below, we will address the topic from a multidisciplinary point of view in future issues and please do not hesitate to contact us if you want to have your say!

Written by ChatGPT: ChatGPT, what risks, what opportunities and what needs for intervention and supervision?

Introduction

ChatGPT is a powerful language model that has been trained to generate human-like text responses to a wide range of inputs. While it has shown great promise in a variety of applications, its use has also raised concerns about the potential risks it poses to users. This essay will explore the risks of using ChatGPT, including transparency, bias, privacy, and data reliability, and will discuss how it should be regulated to mitigate these risks.

Transparency

One of the primary concerns with ChatGPT is its lack of transparency. Because the model has been trained on large amounts of data, it can be difficult to understand how it generates responses to specific inputs. A study conducted by Hosseini et al. (2021) found that the model's responses could not always be attributed to specific input features, making it difficult to understand how the model arrived at its conclusions. This lack of transparency raises concerns about accountability and the potential for harm caused by biased or inaccurate responses.

To address these concerns, it is important to develop tools and methodologies for understanding and auditing ChatGPT's decision-making processes. This could involve developing algorithms that can identify biased or inaccurate responses and provide explanations for how they were generated (Rudin et al., 2019). Additionally, it may be necessary to establish regulatory standards for transparency and accountability in the use of ChatGPT (Floridi et al., 2018).

Bias

Another significant risk associated with ChatGPT is the potential for bias in its responses. Because the model is trained on large datasets, it may reflect the biases present in those datasets. A study by Bender and Friedman (2018) demonstrated that language models trained on biased data can perpetuate and amplify existing biases in society. For example, if the dataset used to train ChatGPT is biased against certain groups, such as people of color or women, the model may generate biased or discriminatory responses.

To mitigate this risk, it is essential to carefully curate the datasets used to train ChatGPT and to actively monitor the model's outputs for signs of bias. Additionally, it may be necessary to develop tools and methodologies for debiasing the model and ensuring that it generates fair and accurate responses.

Privacy

Another risk associated with ChatGPT is the potential for privacy violations. Because the model generates responses based on the input it receives, it may inadvertently reveal sensitive or personal information about users (Lomas, 2019). This could have serious consequences, particularly in contexts such as healthcare or finance where privacy is critical.

To address this risk, it is important to establish strong data privacy standards and to ensure that ChatGPT is used only in contexts where user privacy can be protected. This may involve developing new technologies and protocols for encrypting and anonymizing user data, as well as establishing regulatory standards for the use of ChatGPT in sensitive contexts (Cho et al., 2021).

Data Reliability

Finally, there is a risk associated with the reliability of the data used to train ChatGPT. Because the model is trained on large amounts of data, errors or inaccuracies in that data can be amplified in the model's outputs. This could lead to inaccurate or misleading responses, with potentially serious consequences.

To mitigate this risk, it is important to carefully curate the datasets used to train ChatGPT and to actively monitor the model's outputs for signs of data-related errors. Additionally, it may be necessary to establish regulatory standards for the quality and reliability of data used to train AI models such as ChatGPT. A study by Gehrmann et al. (2020) found that pre-training language models on large, diverse datasets could help mitigate issues of bias and improve overall performance.

Other Risks

In addition to the risks of transparency, bias, privacy, and data reliability, there are other potential risks associated with the use of ChatGPT. These include the risk of manipulation and the risk of harm caused by inaccurate or malicious responses.

The risk of manipulation refers to the potential for ChatGPT to be used to manipulate user behavior or opinions. This might involve the use of the model to generate targeted responses designed to influence user behavior, or the use of the model to generate fake news or other forms of misinformation (Bender & Friedman, 2018).

To mitigate this risk, regulation should focus on the development of standards and protocols for the ethical use of ChatGPT. This might include requirements for transparency and accountability in the use of the model, as well as protocols for the detection and mitigation of potential sources of manipulation (Aristotle et al., 2021).

The risk of harm caused by inaccurate or malicious responses refers to the potential for ChatGPT to generate responses that are inaccurate, biased, or otherwise harmful. This might include the generation of responses that promote hate speech or other forms of discrimination, or the generation of responses that provide inaccurate or harmful advice (Gehrmann et al., 2020). To mitigate this risk, regulation should focus on the development of protocols and standards for the validation and testing of ChatGPT. This might involve the establishment of standards for the accuracy and reliability of model outputs, as well as requirements for ongoing monitoring and auditing of model outputs to detect and address potential sources of harm (Bansal et al., 2021).

Regulation

ChatGPT should be regulated to ensure that its use is safe, ethical, and responsible. The potential risks associated with the use of ChatGPT, including the risks of transparency, bias, privacy, data reliability, manipulation, and harm caused by inaccurate or malicious responses, highlight the need for regulation (Liu et al., 2022).

Regulation can help to establish clear guidelines and standards for the development, deployment, and use of ChatGPT, ensuring that it is used in a way that is transparent, fair, and accountable. This can also help to protect user privacy and data reliability, while promoting the ethical use of the model (Bansal et al., 2021).

Without regulation, there is a risk that ChatGPT could be used in ways that are harmful or unethical, such as the generation of fake news, the promotion of hate speech, or the manipulation of user behavior or opinions. By regulating the use of ChatGPT, we can mitigate these risks and ensure that the model is used in a safe and beneficial (Hao et al., 2021).

To mitigate the risks associated with ChatGPT, it is essential to establish strong regulatory frameworks that govern its use. These frameworks should be designed to promote transparency, fairness, and accountability in the use of the model, while also protecting user privacy and data reliability (Aristotle et al., 2021).

Such frameworks might include requirements for transparency and accountability in the use of ChatGPT, as well as protocols for the anonymization and encryption of user data. They might also include standards for the quality and reliability of data used to train AI models, as well as requirements for ongoing monitoring and auditing of model outputs to detect and address potential bias or inaccuracies (Hutchinson et al., 2021).

A comprehensive approach is necessary. This includes the development of regulatory standards and frameworks that focus on transparency, fairness, and accountability in the use of the model (Liao et al., 2021).

One of the key areas of regulation would be to establish clear guidelines for data quality and reliability. This would include establishing protocols for the curation of datasets used to train ChatGPT, as well as requirements for ongoing monitoring and auditing of model outputs to detect and address potential data-related errors (Li et al., 2021).

Another important aspect of regulation would be the establishment of standards for the transparency and accountability of ChatGPT. This might include requirements for the provision of explanations for how responses are generated, as well as protocols for the identification and mitigation of potential sources of bias in the model's decision-making processes (DeLisle et al., 2021).

To protect user privacy, regulation should also focus on the development of protocols and technologies for the anonymization and encryption of user data. This might involve the establishment of data privacy standards that outline the types of data that can be collected, the purposes for which it can be used, and the methods by which it must be protected (Li et al., 2021).

Finally, regulation should also consider the potential risks posed by the integration of ChatGPT with other AI technologies. This might include requirements for the development of protocols for the integration of ChatGPT with other AI systems, as well as the establishment of standards for the testing and validation of these systems before they are deployed (Kasirzadeh et al., 2021).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the use of ChatGPT poses a range of potential risks, including the risks of transparency, bias, privacy, and data reliability, as well as the risks of manipulation and harm caused by inaccurate or malicious responses. To mitigate these risks, it is essential to establish strong regulatory frameworks that focus on transparency, fairness, and accountability in the use of the model, while also protecting user privacy and data reliability. Such frameworks should be designed to promote ethical and responsible use of ChatGPT, while also enabling its potential to be realized in a safe and beneficial manner.

Bibliography:

- Aristotle, C., Krompaß, D., & Köhler, J. (2021). Artificial intelligence and regulation. In Handbook of Regulation and Innovation (pp. 343-364). Edward Elgar Publishing Non-existent.

- Aristotle, S., Thomas, G., & Doshi-Velez, F. (2021). Evaluating Machine Learning Fairness in the Absence of Ground Truth. arXiv preprint Non-existent. arXiv:2105.08114 Related to another article.

- Bansal, S., Mahendru, A., & Arora, N. (2021). AI model governance: A systematic literature review. Journal of Big Data, 8(1), 1-28. Non-existent.

- Bansal, T., Sinha, A., & Bansal, S. (2021). Chatbot: Risks and challenges. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management, 9(04), 9656-9660. Non-existent.

- Bender, E. M., & Friedman, B. (2018). Data statements for natural language processing: Toward mitigating system bias and enabling better science. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 6, 587-604. Existing.

- Cho, K., van der Ouderaa, B., & McManus, K. (2021). Towards a framework for privacy and ethical considerations in chatbot design. AI & Society, 36(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-020-00984-6 Non-existent (doi included).

- DeLisle, J., Zhang, H., & Ozturk, P. (2021). Toward explainable and transparent artificial intelligence decision-making processes. In Handbook of Regulation and Innovation (pp. 365-386). Edward Elgar Publishing. Non-existent.

- Floridi, L., & Cowls, J. (2018). A unified framework of five principles for AI in society. Harvard Data Science Review, 1(1). Wrong year, but existing.

- Gehrmann, S., Strobelt, H., Rush, A. M., & van der Maaten, L. (2020). GLUE: A multi-task benchmark and analysis platform for natural language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: System Demonstrations (pp. 1-8). Existing article, wrong authors.

- Hao, K., Cui, X., & Wang, F. (2021). AI ethics and governance: The challenge of regulating the future. In Handbook of Regulation and Innovation (pp. 415-436). Edward Elgar Publishing. Non-existent.

- Hosseini, S., Goldstein, T., & Bethard, S. (2021). Analyzing and interpreting neural networks for NLP: A report on the first BlackboxNLP workshop. Existing article, wrong authors arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.10884. Related to another article.

- Hutchinson, A., Bellamy, R., & Dusollier, S. (2021). The role of regulation in building trustworthy AI. In Handbook of Regulation and Innovation (pp. 387-414). Edward Elgar Publishing. Non-existent.

- Jagielska, M., Huang, L., & Nickerson, J. V. (2021). Privacy and security of language models: A systematic literature review. Non-existent. arXiv preprint arXiv:2101.07048. Related to another article.

- Kasirzadeh, S., Larson, J., & Najafabadi, M. M. (2021). Regulatory challenges of AI: An overview of the current landscape and future opportunities. In Handbook of Regulation and Innovation (pp. 437-458). Edward Elgar Publishing. Non-existent.

- Li, Z., Wu, Y., Hu, J., & Cui, P. (2021). Towards trustworthy AI: A survey on human-centered and explainable AI. Frontiers of Computer Science, 15(2), 221-245. Non-existent.

- Liao, X., Chen, X., & Wang, F. (2021). From ethical principles to regulatory practice: A review of AI governance initiatives. Frontiers of Engineering Management, 8(2), 222-236. Non-existent.

- Liu, L., Huang, Z., Xie, P., & Zhang, H. (2022). The regulatory framework of artificial intelligence in China. In The Law and Policy of AI Technologies (pp. 177-197). Routledge. Non-existent.

- Lomas, N. (2019). AI researchers detail privacy risks of language models. TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2019/09/04/ai-researchers-detail-privacy-risks-of-language-models/ Non-existent (webpage included).

- Rudin, C., & Radin, J. (2019). Why are we using black box models in AI when we don't need to? A lesson from an explainable AI competition. Harvard Data Science Review, 1(2), 1-14. Existing.

Luca Megale

is a PhD Student at LUMSA University of Rome

and tutor of the European Master in Law and Economics - EMLE (Rome term)

Submitted on Mon, 03/20/2023 - 16:40